UPDATE (Nov. 2012): In response to complaints made about the recently-announced $300 price point of the Wii U, I have added an addendum to this article addressing console prices.

UPDATE (July 2013): The article has been revised to take into account the announced price points of the PS4 and Xbox One as well as statements from Sony and MS regarding the price of next-gen software. The console price charts have been updated to account for those new systems.

Update (Dec. 2013): Software price charts have been rebuilt using a spreadsheet program to make them look a bit nicer than the old charts, which were made by hand in MS Paint. Prices were also updated, though the difference from the older figures are negligible given that it has only one extra year of inflation.

Update (Feb. 2015): Updated to add pricing information on PS4 & Xbox One games. Software price charts updated to 2014.

(Note: All prices cited in the article are in U.S. dollars.)

If you read any online discussion about video gaming, you’ll see all sorts of arguments and complaints. Some are classic standbys, such as “Console vs. PC” or “Nintendo vs. PlayStation vs. Xbox” or the relative merits (or lack thereof) of the business practices of EA, Activision, Sony, Microsoft, etc. However, one thing that appears to unite a plurality if not outright majority of gamers (or at least those who post their opinions in online forums), the thing that draws their ire seemingly more than just about anything else, is the price of a video game. Many people believe the $60 price point is “too high” and some even believe games cost more now than ever. But are complaints about game prices valid? Do games cost too much? Do they cost more now than they did in the past? The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that the answer to these questions is a resounding “No.”

Now, it is true that $60 is a lot of money to be throwing around. Money that could be spent on a lot of other things like food, gasoline, & other necessities or other forms of entertainment. Forking out sixty bucks is a serious investment, and if we find we don’t like the game, then we’ve essentially lost out on most of that money (you probably won’t get all that back selling it off to someone else). The fact that a lot of people were hit hard by — and many of them still feeling the effects of — the recession of the late 00s certainly doesn’t help the public perception of the $60 price point. But I contend that complaints about game prices are overblown and based on false assumptions. Personal issues regarding said industry, such as resentment due to being burned by a bad purchase and/or general mistrust/dislike of big business (i.e., the “corporations are bad” mindset) may be a factor influencing people’s opinions as well. For example, many people claim that game companies are engaging in “price gouging.” This sometimes gets ridiculous to the point of unintentional parody. Case in point: Some guy on Yahoo who was complaining about game prices described game companies as, and I quote, “video game robber barons” whose “drive for profit is wrecking the industry.”

Let’s examine first the claim that game prices are at an all-time high. The gamers who are complaining that games are more expensive than ever have a serious lack of historical perspective, and if I had to guess, many if not most of them are either too young to know better or they simply haven’t been gamers for very long. It’s also possible they’re just being hyperbolic, something many gamers are prone to do (e.g., when an 8/10 rating is decried as “terrible” when in fact that’s actually a very good rating).

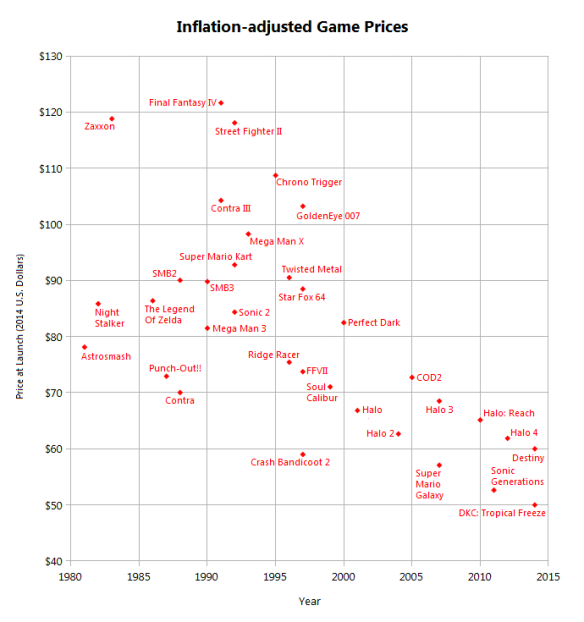

As it turns out, though, $60 is hardly an unusual price point for a new console game (nor do all new games today cost sixty bucks; $50 is the standard for Wii titles, and even some new 360 and PS3 titles can go for that as well), and you can go back 20 years and find games that cost just as much if not more. For example, see this chart I made showing prices of select console games of note going all the way back to the second generation (I’m leaving out the Neo Geo for reasons that should be obvious to anyone who knows of the system):

As you can see, the price points of today go all the way back to the early 90s, while back in the 80s prices were typically in the $30 to $50 range. You’ll also notice that pricing was far less standardized back in the 20th century, with titles on the same system having price points commonly spread across a $15-20 range. Games for old second-gen consoles like the Intellivision and Atari 2600 usually ran from $25 to $40, with some outliers going even higher (like $50 for Zaxxon on the Colecovision). On the NES, prices typically ranged from $30 to $50, with $35 being perhaps the most common price point. By the 16-bit era, the asking price for a game was anywhere from $50 to $70 (a rare few went even higher: Virtua Racing on the Genesis cost $100 new in 1994, or nearly $160 in 2014 dollars, possibly a record for a game not on the Neo Geo). These prices carried over to the fifth generation. Nintendo 64 games typically ran for $60 to $70. Meanwhile, earlier games for the original PlayStation typically ran from $50 to $60, but by 1997 were usually going for $40 to $50 (more on this difference later). Since the turn of the century, prices have become far more standardized. The price of most new titles during the sixth generation was usually $50, while during the seventh generation $60 was the norm for Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 games while $50 was the standard for most new Wii titles. In the current (eighth) generation, the $60 price point has remained standard for most new PS4, XBO, and Wii U games.

Of course, even though prices are much more standardized there are outliers. For example, Sonic Generations for the 360 & PS3 and Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze for the Wii U both launched at $50). Some remakes of older games also cost less than the $60 standard, e.g., Wind Waker HD cost $50 when it came out, and some upcoming remasters cost only $40. While some game cost less than the $60 standard, except for the occasional special edition releases that certain games get (which usually run anywhere from $70 to $150, depending on how extravagant it is), you’re not going to be seeing any contemporary console game go for more than $60 new. The days of new bare-bones releases costing $70 like some did on the SNES, Genesis, and N64 are over, and there’s no sign of the $70 price point making a comeback anytime soon.

So, while a lot of gamers might not believe it, it’s a fact that the average price point of games is not at a historical high, and many games for the SNES, Genesis, and N64 could cost $60, sometimes more. The claim that “games cost more than ever” is quite simply false. It’s not an opinion, but an objective fact.

But wait a second! Aren’t we forgetting something?

Often neglected in discussions comparing historical and current prices of various consumer goods and services is a very important economic factor: Inflation. Anybody who’s passed high school economics knows about this phenomenon: as time goes by, the value of a dollar goes down. When comparing prices of goods from two or more different years, it is important to use “constant dollars” (e.g., “1980 dollars” or “2014 dollars”) to reflect the relative value of a dollar in one year versus its value in another.

For example, you sometimes might hear a Baby Boomer talk about how gas was only 50 cents a gallon 40 years ago and how today’s national average gas prices (which have fluctuated widely over the last decade, but averaged between $3.20 to $3.90 from 2011 through most of 2014 before dropping to below $2.50 in Dec. 2014) are just outrageous, but 50 cents was worth a lot more back in the early 70s than what it’s worth today. To be exact, 50¢ in 1972 dollars is worth $2.81 in 2015 dollars, more than current (Feb. 2015) prices. If you just look at nominal prices for gasoline, you’re not getting the whole picture. Comparing it to inflation-adjusted prices tells a different story, one that tells us that while gas prices have indeed been quite high for the past decade, they’re certainly not unprecedented, but rather they are comparable to those during the early 80s when the cost of gasoline spiked as a result of the 1979 energy crisis (in fact, as automobile fuel economy has improved over the decades, the inflation-adjusted cost per mile is actually lower than it was in the early 80s, though still considerably higher than in the late 90s; see here). As of early 2015, inflation-adjusted gasoline prices are approaching the lows of the 90s.

Or to use food items as an example, when I was in grade school in the latter half of the 80s, a candy bar cost roughly half of what one does today, but a dollar was also worth about twice as much 25 years ago than it’s worth today, so in reality if I bought a bar of candy today, it’d be comparatively no more expensive than one I ate when I was in second grade. Take-out pizzas from Domino’s or Pizza Hut cost $10-12 dollars in the early 90s just like they do today and the price tag of a 2-liter of soda has remained rather stable at least since I was in high school, which also makes them technically less expensive now than they were in the 90s. As the old saying goes, a dollar just doesn’t go as far these days.

So, now that that little economics lesson is out of the way, let’s take the effects of inflation over the last several decades and apply it to data shown in the first chart:

As you can see, when you take inflation into account, the idea that games are more expensive than ever before is not only categorically false, but the inverse is actually true. We’re actually paying less on average than we were in decades past. In many cases, a lot less. If you think paying $60 for Battlefield 4 or Skyrim or GTAV was bad, imagine paying the equivalent of $115 in today’s dollars for Street Fighter II when its SNES port launched in 1992. Nobody in their right mind would pay over $100 for a game today, yet that’s what millions of people were willingly paying the equivalent of back then (and the economy wasn’t exactly in the best of shape in the early 90s, either). Only games towards the low end of the normal price range of their eras can claim to approach or be on par with the price of a new game today. Even those $40 PS1 games are on par with current game prices ($40 in 1996 dollars is about $60 today, while in 2000 dollars it’s about $55). While many modern games do have DLC, which can up the amount you spend on a game, said content is entirely optional, and even after factoring in the cost of DLC that still only puts these games on par with early 90s games.

Average inflation-adjusted prices for video games peaked in the early 90s and have been on a steady decline ever since. Even ignoring especially high-priced titles like Street Fighter II or Final Fantasy IV (originally called Final Fantasy II when it launched in America), prices were still higher on average in the past. A game like Sonic 2 that was only $50 in 1992 was worth the equivalent of over $80 in today’s dollars. Even titles that were considered budget price after being around for several years would, after accounting for inflation, have prices comparable to a brand new game today. For example, back in the early 90s near the end of its life cycle, the NES had a reduced-price “Classic Series” line, which included Metroid and The Legend of Zelda. The asking price for these games was $30 even in 1993, which is the equivalent of about $49 today. That’s right: even two years after the SNES launched, a budget NES title cost almost as much as some new games do today when you correct for inflation.

Given all these facts, one wonders if the complaints about game prices were more, less, or about the same in frequency and intensity 20 years ago as they are today. There’s no way of knowing for sure, though, since that was years before the internet became a popular communications tool (and the WWW didn’t even exist until 1993). From my own personal experience, though, I don’t recall people really complaining about game prices much if at all. I know I willingly and without complaint paid $60 or more for N64 games when I got my first part-time job in 1998 (and minimum wage was much less back then — $5.15/hour vs. $7.25/hour today — so I had to work more hours to buy a game than some part-timer earning minimum wage today would have to work). But here in the internet age, there are certainly a lot of people online complaining about how much games cost. Perhaps they’re just a vocal minority? Who knows?

Millions of people paid $70 for this game. In 1992!

Now, you might be asking “Didn’t games cost a lot more to manufacture back then because they used cartridges instead of discs? Isn’t that why they were more expensive?” Well, yes and no. ROM cartridges did indeed cost considerably more to manufacture than optical discs — according to one source, an N64 cart cost over $10 to make, vs. about $1.50 for a PS1 disc —, and those manufacturing costs were almost certainly factored into the retail price of a game, hence why new N64 games averaged at least $10 more than new PS1 games.

But even if we completely ignore the cartridge format and stick purely to games released on disc, the fact that games are getting on average cheaper still stands. During the 16-bit era when the first CD-based systems/add-ons like the Sega CD were introduced, the games released for them could often go for upwards of $50 or more. An example not shown in the above graphs was 1992’s Lords of Thunder for the TurboDuo, which was the same price as Sonic 2 (shown in the charts), which was also a 1992 release. As mentioned earlier, early in the PS1’s life new games for the system frequently cost $60, and during the remainder of the 90s, disc-based games could still run anywhere from $40-50. During the sixth generation $50 was the standard (and remained the standard for Wii games), and that has increased to $60 for 360, PS3, Wii U, PS4, and XBO games.

But when you adjust those prices for inflation, you’ll see that average prices for new titles for disc-based systems have actually been trending downwards over the past 20 years. If you bought COD: Ghosts, Skyrim, The Last of Us, Mario Kart 8, or Destiny brand new on day one, you’ll have spent less in relative terms than you would have on Lunar: The Silver Star, Final Fantasy VII, Sonic Adventure, or Halo: Combat Evolved when they debuted.

But manufacturing costs are not the only factor one must take into account when discussing game prices, and to focus on them misses the bigger picture. There’s all sorts of other costs involved in making a video game: marketing and distribution costs, the retailer’s cut, fees to the console manufacturer (for third-party titles), licensing costs for games based on other IPs (when applicable), and so forth. But the biggest cost of all for modern games is the production/development costs. Sure, discs are much less expensive to manufacture than a cartridge, but games are far, far more expensive to develop today than they were in previous generations. Development budgets for most games released at retail (especially so-called “AAA” games) have exploded over the last couple decades as technology has advanced and games have consequently become ever more sophisticated, and they have now surpassed manufacturing costs, even if you compare it to the cost of manufacturing old Nintendo 64 cartridges (and as mentioned earlier, manufacturing costs are included in the retail price of a game, whereas development costs are not).

Unlike the retail price of an individual copy of a game, the cost of producing a game has far outstripped the inflation rate, increasing by two entire orders of magnitude over the last 20 years. In the 16-bit era, a game might only cost at most $300,000 to develop and have a production crew of maybe twenty or thirty people. During the fifth generation, the introduction of 3D graphics drove the potential dev costs of games to over a million dollars, and sixth-gen games could cost several times that. Today, a major AAA title can take well over a hundred people to make and can have a development budget of around $20-30 million. Some really big-name games are starting to get budgets that approach those of major motion pictures, costing upwards of $100 million or more, though such expensive games are very rare and the total cost likely also includes marketing costs.

Cartridges were only part of the problem with game prices. Manufacturing costs have now been supplanted and surpassed by rising development costs.

That big-name console titles can cost a hundred times more to develop today than they did 20 years ago, yet those increased costs have not had a substantial effect on the price of a video game, is rather surprising. Perhaps this is likely due to the fact that games are, despite being way more expensive to make, still quite profitable when they sell well. For example, Halo, Grand Theft Auto, and Call of Duty games sell so well they probably make back their entire production and marketing costs on launch day and then some, and their total grosses are comparable to the worldwide grosses of successful blockbuster films. Even most games that sell “only” between 1 and 3 million copies are often very profitable.

Of course, the key words in the above paragraph are “when they sell well.” Just like how not every movie is profitable for a Hollywood film studio, for every game that turns a profit there’s several other games that end up not being profitable and thus lose the publishers and studios money (according to the Electronic Entertainment Design and Research institute, only 20% of games will turn a profit, and that’s only for titles that actually make it to store shelves, which is in turn only about 20% of games that go into development). Most of us probably never even hear of some of these games, but since literally hundreds of console games are released each year, it’s a given that many if not most will be obscure titles that fail to sell (though to be fair many of those titles probably don’t cost nearly as much to make as do more high-profile titles).

Another factor that probably keeps the nominal prices of games from going up drastically over time is the increased user base. Video games are more popular and mainstream than ever. Over 260 million seventh-gen consoles have been sold globally to date, more than any prior generation. The PS3 & 360 alone are likely approaching the 170 million mark combined. The number of games sold this generation is also higher than ever before, with around 2.3 billion discs being sold to date across the three major home consoles over from 2005 to 2012. Furthermore, while it was once rare for a game to sell over 10 million copies (SMB3, Super Mario 64, and Gran Turismo are the only 20th-century console games not originally bundled with a system to pass that mark), there are now at least two games released each year to sell over 10 million. All told, annual revenues for the seventh generation are by far the highest of any console generation in history, and are obviously still more than sufficient to fuel an industry whose costs have steadily increased over time.

Now, it’s obvious that development costs cannot and will not continue to grow exponentially. Otherwise we’d be looking at games with billion-dollar budgets in 5-10 years. In fact, it’s possible that increased optimization and efficiency of the development process, as well as the increased ease of development on the PS4 and XBO may cause production costs to slow in their growth and start to plateau. However, it’s also likely that production costs, at least for major AAA titles, could continue to increase as gamers crave ever more cutting-edge experiences with better AI, bigger worlds, and more advanced graphics.

But it remains to be seen as to how much, if any, average development costs will continue to rise. Recently, an EA exec has stated that he expects dev costs to increase only 5-10% for next gen, and Ubisoft CEO Yves Guillemot said “In the first two years, I expect [next-generation dev] costs to remain the same.” However, later in the same interview Guillemot says he expects dev costs to start to increase later in the eighth generation, saying “we’ll have to spend more money to take advantage of all the possibilities these machines are bringing, and it can grow quite fast,” and in a 2009 interview, he said he expects median dev costs to increase to around $60 million, a two- to three-fold increase from average seventh-gen costs (though that was long before the first PS4 and XBO dev kits started being sent out).

So, there’s a good possibility that at some point in the eight generation we’ll start to see non-trivial increases in development budgets. Whether that translates to an increase in the MSRP of a new title remains to be seen. So far $60 continues to remain the norm for new games, and no increases in retail prices for PS4 & XBO games are on the horizon. If production costs do grow noticeably, at $60 a copy (of which the publisher may see only $48 of in revenue, as according to Forbes the typical retailer cut is 20% of MSRP) most popular titles should still remain fairly profitable after around just 2 or 3 million copies sold, but that still won’t change the fact that if costs continue to grow, the more copies a game will need to sell just to break even. The return of the $70 price point might not happen in the eighth generation and there’s no signs of increase on the horizon, but it’ll likely happen sooner or later.

In any case, even if we do start seeing $70 games from some publishers later this generation, it’s already been established that some games debuted with a $70 price point in the early 90s, when $70 was equal to about $120 in today’s dollars, and this is despite those older games costing only a tiny fraction what they do today to develop. Even if prices went up $70 tomorrow, then sure, we might feel a bit of a bite from that right away. But, just as the chart shows for when MS and Sony started charging $60 for 360 and PS3 games when those systems debuted instead of the $50 they charged for Xbox and PS2 games, the effects of inflation will erase that temporary increase after a few years.

For example, the $60 people paid back in 2005 for 360 launch titles like Call of Duty 2 is the equivalent of almost $73 in 2014 dollars, roughly the same as a next-gen title assuming there’s a $10 hike to the standard price. As another example, while the price of games in the Halo series (several of which are shown in the price charts above) jumped from $50 on the original Xbox to $60 on the 360, the effects of inflation have served to flatten out the price disparity; Halo 3’s inflation-adjusted price is less than Halo 1’s adjusted price, and Halo 4 was the cheapest in the series to date. So, assuming inflation rates remain constant, $70 in 2020 will be the rough equivalent of $60 today. And if all next-gen games stay $60, well, that means that by decade’s end we’ll be spending about as much for them as we do on a Wii game today in relative terms. But even if we don’t see an increase to $70, we shouldn’t expect them to ever go below $60 ever again. The steady increases in production costs over time simply won’t allow for it.

Now that I’ve addressed the history of game prices and the reasons why games cost what they do — the “Are games more expensive than ever?” question —, let’s tackle the question “Are games too expensive?” Some gamers argue that they are simply getting a lot less bang for their buck. “Okay,” they might say, “So games aren’t really more expensive, but still, they’re not worth $60.” While the relative worth of any given game is largely subjective, I’d still argue that the idea that we’re getting less for our money is not true, at least purely in terms of a money/time ratio. Except for RPGs and certain action-adventure games (e.g., The Legend of Zelda), most games from back in the 80s and early 90s were designed to where they could easily be beaten in a single session. Most old-school platformers, shoot-’em-ups, and beat-’em-ups could be beaten in around two or three hours, sometimes less.

Fast-forward to today. You have games like the Halo series, which are not only just as fun as any classic game, but also offer massive 8-hour single-player campaigns and online multiplayer that can be replayed endlessly, and in more recent titles in the series there’s new play modes like Forge mode where you can modify or create your own maps, and Firefight, which is an arcade-style survival mode. BioShock has an incredible story, an engaging, immersive world, and gameplay that allows for many different play styles, and though it only has its single-player campaign, it can take 15-20 hours to beat it if you’re going for 100% completion (including finding all the audio logs and other secrets). The Last of Us is one of the most critically-acclaimed games of the past decade and according to most sources can take 15 hours to beat. A contemporary game whose single-player mode lasts only five or six hours is often labelled as “short,” yet it’s more than what we usually got back in 80s & 90s.

Games have become so much more advanced than they used to be and typically offer much more content. We have games like Battlefield that offer massive multiplayer maps with fully destructible environments. There are games like Far Cry 3, Skyrim, GTAV, and Red Dead Redemption that offer massive open-world environments with tons of things to do, enough to keep someone occupied for days if not weeks. We’ve gotten games like Super Mario Galaxy and LittleBigPlanet that offer incredibly fun and innovative platforming experiences that would have been difficult if not impossible to create in prior generations. To argue that we’re not getting our money’s worth when we buy any halfway decent game, especially considering that we’re technically paying less for games these days, is a stretch at best.

Even compared to other forms of entertainment, it’s hard to argue that games aren’t worth the asking price. Just compare that $60 game that can entertain you for 6 or 8 hours per playthrough (sometimes way more, depending on genre and/or if you play lots of MP if that’s an option) to $12 for a music CD that might only last an hour, or $9 for a one-time-use ticket to a 2-hour movie (double that for IMAX screenings, and don’t forget drinks and popcorn!), or $20+ for that same movie when it comes out on Blu-ray. If today’s games aren’t worth $50-60, then the games of yesteryear sure as hell weren’t. Personally, I think that compared to 20 years ago, many of the games we get now are a pretty damn good deal in terms of sheer quantity of content. We are getting more bang for our buck these days compared to most older games, and we are getting our money’s worth as compared to most other forms of entertainment when it comes to a cost per hour of entertainment analysis.

Of course, the perceived value of a product also includes various subjective factors, and reducing it to a formula of price divided by hours of entertainment is overly simplistic, especially since games are interactive and not completely fixed and invariable experiences like movies or music. Game length can vary based on difficulty, play style, and whether one goes for 100% completion. It can also vary between and even within genres. It’s also hard to quantify multiplayer since there is no real end-game and matches are typically short affairs. Some gamers prefer shorter, more focused action experiences that can be beaten in a couple of sessions, while others prefer sprawling open worlds or epic RPGs that take weeks to complete, and others still may focus almost entirely on multiplayer games, logging in however many 5-10 minute matches they have time for in a day. The replay value of a given title can vary from person to person. But based on the sheer amount of content even in shorter AAA games as compared to movies, music, or even older games from the 2D era, it’s hard to argue that modern games cost too much.

Halo: Reach was totally worth $60 (actually $80 in my case, as I got the Limited Edition).

Gamers keep asking for more and more but want to pay less and less. Many of us complain about how game publishers are charging us $60 for a game, and they sometimes speak of it as if it were highway robbery or something. But you know what? On the whole, we are paying less and getting more compared to decades past. Right now is probably the best and least costly time in the history of video games to be a gamer. We have so many options available for us these days, with access to certain tools and services that didn’t even exist back in the 80s and early 90s.

If we’re not willing to wait a while for a game’s retail price to inevitably be reduced (many notable titles can often be bought brand new for $40 or less just a year or so after launch, sometimes much sooner), we can buy a used copy for at least somewhat less than MSRP at most places that sell games (and GameStop’s return policy allows one to return a used game for a full refund within 7 days, unlike when they purchase a new game). The used games market as it exists in retail today was essentially nonexistent 20 years ago, and didn’t really start to emerge until the late 90s. We have the internet, which provides us with a wealth of information far beyond what was provided by monthly print periodicals like Nintendo Power, GamePro or EGM back in the day. For example, we can go online and watch gameplay videos and read a plethora of in-depth articles and reviews and otherwise more fully research a title before we buy it, and all this information comes at us in real time as the news comes. Sometimes we even have the option of downloading demos of games from XBL or PSN before we buy them (while it would be nice if they were more common, there are valid economic reasons why they aren’t). We even have digital stores like the Xbox Marketplace, PlayStation Store, and the Nintendo eShop (which contains the Virtual Console), where for just a few bucks one can download games like Mega Man 9, Journey, The Walking Dead, Resogun, Shovel Knight, or any of a number of classic arcade and console titles, which is great for more budget-conscious gamers. There’s also the tried and true practices of renting games or borrowing them from a friend.

So, before you start issuing complaints about game prices, remember to have a little perspective and try to understand that current prices are not “rip-off” or whatever you feel like calling them. $60 is a fair price all things considered, and since video games are an industry with slim profit margins and increasing costs, it’s not likely to go down. All your big-name AAA titles like COD, GTA, Assassin’s Creed, and Uncharted cost that much for a good reason. It’s not a matter of greed. It’s not price gouging. It’s just the way capitalism works. A company has to make a profit to stay in business, and there’s good reason to think that a substantial reduction in retail prices would cut into their profits. That is unless you think price elasticity is sufficient to where sales would double if launch prices were cut in half, but I doubt that would be the case.

If you don’t want to pay $60 for a new title because you feel games aren’t worth that much, then you don’t have to. You have options available to you, some of which I mentioned earlier. If you blind-buy a game brand new only to discover that it’s a stinker or has some other element that you disapprove of (e.g., on-disc content locked behind a pay wall) and you feel that your $60 was not well-spent, well, Caveat emptor. Whenever you pay for an entertainment product, you assume the risks associated with such an act, i.e., you might end up not liking it. Sturgeon’s Law Revelation applies just as much to video games as it does to any other kind of entertainment, so it’s not a big surprise that not every game out there is a perfect 10-out-of-10. This was true in decades past, it’s true today, and it will continue to be true in the future. I’m aware of this, and this is why I’m a discriminating shopper, unwilling to part with $60 unless I’m absolutely sure I’ll like the game, and for titles I’m less certain of I’m willing to wait for the price to drop, or I’ll just rent or borrow it. I also always at least try to properly research every title I buy. It’s worked out so far, as since 1998 when I first started buying games with my own money I have not once bought a game that I didn’t like (I have been burned at the theater on occasion before, though, seeing a movie I thought I’d love and ended up hating it, but I didn’t go around calling Hollywood a bunch of thieves or crooks). If I just grabbed any old CD, movie, or book off the shelf, payed full price for it, and then found I didn’t like it, is it the publisher’s fault for releasing something I consider “bad,” or is it my fault for not being a more discriminating consumer? The same principle applies to video games.

But as long as millions of people pre-order and wait in line for the midnight launch of the latest AAA blockbuster and pay the asking price for a game, and as long as game companies feel that they need to charge the prices they do in order to stay profitable, then that’s what the price of games shall continue to be. The fact that Call of Duty games routinely sell many millions of copies at $60 a pop justifies said price point (and justifies Activision’s practice of having a new COD game every year), and that’s just one big-name franchise. Whether any of us like it or not is quite frankly irrelevant. Over a billion dollars in revenue from a single title speaks louder and carries more weight than the complaints of some anonymous disgruntled gamer. We are not entitled to having AAA console games cost $20 or $30 brand new on day one just because we go online and say we are. Games will not have price points so low that those producing them can’t remain financially viable by selling at those prices (it all has to be paid for somehow). It doesn’t matter if you personally are either unwilling or unable to buy big-name console games new. I’ve been strapped for cash for most of my adult life, and I’ve had to do without for long stretches of time, generally restricting new purchases to one or two games I consider absolute “must-haves.” For other games I simply wait until their price goes down (I bought Alien: Isolation and Far Cry 4 for $40 only three months after launch at Amazon) or buying them second-hand through the used games market (as I did with BlazBlue and F.E.A.R.). As a lifelong gamer, it certainly sucks, and there’s many titles I haven’t gotten around to playing, but hobbies are not necessities, and I’m not going to begrudge game companies for charging $60 for a new game.

If games were grossly more expensive in terms of cost per hour of entertainment than movies, music, etc., or the average amount of content in a typical game started declining rapidly (which is really a corollary to the first example), or their inflation-adjusted price had actually been increasing over the last 20 years instead of decreasing, then claims of price gouging would be justified. But they’re not. The $60 we get charged is perfectly reasonable and justified, as I’ve already stated many times (but always bears repeating). If people had a better understanding of the economic realities of the video game industry, they’d probably be less prone to making these accusations.

Sure, there’s plenty of things in the world of video gaming that are worth complaining about. For example, there’s some definitely questionable business practices employed by certain game publishers, such as so-called “on-disc DLC” (probably the most oxymoronic term the industry has ever seen), “always online” DRM, the increasingly aggressive push towards adding “Skinner box” mechanics into a wider variety of games, plus there’s growing industry antagonism towards the used games market and the First-sale Doctrine. There are lots of valid complaints to be made about these things, and gamers should certainly air their grievances regarding them. But the $60 price point for a new game is not an example of game companies being “crooked” or “greedy” or “robber barons.” Microsoft, Sony, Activision, Take Two, Ubisoft, Square Enix, Epic Games, etc., are not the moral equivalent of Lehman Brothers or Enron for charging those prices. If you really step back and look at the situation objectively, complaints about game prices are entirely baseless. They are not more expensive than ever, nor do they necessarily “cost too much”… unless of course you’re living in Australia.

FURTHER READING & RESOURCES

Just Stop! Games Are NOT More Expensive Today

Is the $60 price point too much?

Why Gears of War Costs $60

Video Game Scans @ HuguesJohnson.com (1990s price data)

Wishbook Web (1980s price data)

Rivalry In Video Games (historical data, including development & manufacturing costs; PDF format)

Inflation Calculator @ The Bureau of Labor Statistics

ADDENDUM: A LOOK AT CONSOLE PRICES OVER THE DECADES

When Nintendo first announced the price point of the Wii U — $300 for the 8GB “Basic” model and $350 for the 32GB “Deluxe” model — it was met with some complaints. Some people were proclaiming it was “overpriced” (by what standard?) or that since the Wii cost $250 at launch, so should the “underpowered” Wii U. This brings me to a subject that I neglected in this article, that being the cost not just of the games, but the systems themselves. We saw similar complaints about the PS3’s $500 launch price back in 2006, and now we’re seeing similar complaints about the Xbox One’s $500 price point (and the PS4’s $400 price point to a lesser extent). But how do modern console prices stack up against prices of older systems? Here’s a chart comparing the launch prices of every notable console from the second generation on up to the present day:

In this chart, we see that, while prices are all over the place, most systems debuted at $300 or less, with $200 being the most common price point (though the GameCube, released in 2001, was the last system released at that price). The PS3 has the third-highest price point of any console in history, while the “Deluxe” model of the Wii U is ranked seventh highest and the “Basic” model has the same price point as the Intellivision, PlayStation, PS2, and Xbox 360 “Core” system (the one that lacked a hard drive and came only with composite AV cables). However, let’s take a look at those prices adjusted for inflation:

As we can see, the launch price of the PS3 drops considerably in comparison to the launch prices of other consoles when you correct for inflation. It’s still on the high end, but it’s far from the most expensive system ever. The inflation-adjusted launch price of the 20 GB PS3 SKU is a bit less than the Saturn’s, and considerably less than that of the Atari 2600, Intellivision, 3DO, or the Neo Geo. Early adopters of the system ultimately got somewhat decent deal, as not only did it play Blu-ray discs in a year when standalone BD players were still extremely expensive (they had just been introduced earlier that year, and most retailed for $1000 or more, double the price of the base PS3 model), but it also eventually amassed an incredible library of exclusive titles such as Metal Gear Solid 4, God of War III, the LittleBigPlanet, Uncharted, Killzone, Resistance, and Infamous series, and The Last of Us in addition to tons of great third-party games.

The Wii U fares even better when you take inflation into account. The $300 Basic model is, only marginally more expensive than both the Wii and N64 were when they debuted and is the sixth least expensive console ever, while the $350 Deluxe model is almost exactly as much as both the Sega Genesis and Xbox 360 “Core” system were at launch, and only slightly more than the SNES. Plus Nintendo has historically had a great library of first-party and other exclusive titles on all of its systems, and the Wii U is no exception. Its current library has games like New Super Mario Bros. U, Pikmin 3, The Wonderful 101, Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze, Wind Waker HD, Super Mario 3D World, Mario Kart 8, Super Smash Bros. 4, and Bayonetta 2, while upcoming games include Xenoblade Chronicles X and new Zelda and Starfox games. The Wii U is more than worth the asking price, at least if you like Nintendo games.

So, complaints about the Wii U’s price were hardly justified, as it’s actually one of the least expensive systems in inflation-adjusted terms. Even if we ignore the effects of inflation, it’s not an outrageously expensive piece of hardware. After all, several other popular systems debuted at $300, and Microsoft was still charging $300 for the Xbox 360 (with HDD included) until just before its seventh birthday. As for the PS3, while there might have been some justification for the complaints lodged against its launch price as it was still an unusually high price point, I’d argue that it wasn’t quite as bad as what people were making it out to be. To compare the PS3 to systems that were far more expensive in inflation-adjusted terms, it’s arguably at least as good or perhaps better than the Atari 2600, Intellivision, or Neo Geo were in their heyday, and it’s certainly a vastly better deal than historical footnotes like the 3DO (and other expensive also-rans that aren’t shown on the chart for space-saving reasons, e.g., the CD-i, which debuted in 1991 for $700, or just under $1200 in 2013 dollars).

In inflation-adjusted terms, median console prices were at their highest by far during the second generation, and, not counting poorly-selling and very expensive outliers like the Neo Geo and 3DO, they have been relatively flat amongst post-Crash consoles of a given brand name. This holds true for all next-gen systems as well. Just look at how the PS4 and XBO compare to their predecessors. The PS4 is actually the least expensive PlayStation system ever, just edging out the PS2, while the XBO’s launch price was not that much more than the 360 “Pro” SKU (though it was still more than it should have been, as MS insisted on making Kinect an integral part of the system, not unbundling it until half a year after launch).

In any case, instead of being an early adopter of a system, you can of course always wait a while for the system to drop in price, which they all do. Most systems get their first price cut within a year of launch, and except for the Wii no major system released from the 16-bit era the present has gone more than two years without one. For example, the PS3 gradually dropped in price from $500 at its launch in 2006, to $400 in late 2007, to $300 in 2009, and now it goes for $250 (all prices being for the cheapest SKUs), and classic systems like the Genesis and SNES dropped in price by considerable amounts within two years after launch. The XBO is already retailing for $350 for the Kinect-less SKU. By the end of 2015, we should see $50 to $100 knocked off of the PS4’s price tag. As I mentioned in the main article, you don’t have to buy a game new right when it comes out, and that applies to consoles as well. With only a couple of exceptions (the Dreamcast and the PS4), I’ve never gotten a system right when it first came out, and I instead waited until after a year or two, opting rather to play on friends’ systems.

It’s also important to point out that console prices are quite justified. They are very expensive to develop and manufacture, and in the case of the PlayStation and Xbox lines they have usually been sold at a loss early in their life cycle. The PS3 was estimated to have originally cost over $800 per unit to manufacture, while the Xbox 360 was estimated to cost in excess of $500 per unit, which in both cases is considerably more than their initial retail prices. The PS4 and XBO were initially sold at or slightly below the break-even point. Even the Wii U was sold at a slight loss earlier in its life, which is a first for Nintendo (the GameCube and Wii were cheaper to manufacture than their rivals in their respective generations, and Nintendo was able to sell them at a profit; as for fifth-gen and older systems, I’m not sure if any of them were loss leaders or not). Those initial revenue losses are offset by software & accessory sales and licensing fees for third-party developers.

So, just like with games, there are very good and perfectly valid reasons consoles cost what they do. The simple fact that consoles are initially sold at a loss makes it painfully obvious that console makers are not laughing all the way to the bank with your hard-earned money, pocketing a massive profit. Console makers might take a hit to their profits early on, if only because they know that consumers will only tolerate so high of a price point. Really, who would’ve bought a PS3 if it sold at the $900 price point needed for each system sold to be profitable at launch? So, next time you feel the urge to complain about the price of a console, keep what you have learned here in mind.

So given that, why do they FEEL more expensive for many people? Answer, I think, is that incomes haven’t kept up with inflation, unless you’re in the ‘sort of rich’ ($350,000/yr) or higher income level.

Yeah, SF2 cost what would now be well into the $100 range. but in 1992 we didn’t have a wide swath of the USA in default on their mortgages. Unemployment and underemployment, particularly amongst parents with dependent children was lower. It’s a big problem for the “disposable income”-based industries (video games, movies, etc).

Aye, but I did say that current economic conditions don’t really help many people’s perception of the $60 price point. A lot of people were hurt by the recession of 2008-09, and many are still feeling its effects, though many if not most households were relatively unaffected by the recession (e.g., unemployment peaked at around 10% in fall 2009 and is currently at 8.2% and trending downwards, meaning that the vast majority of the workforce stayed employed; unemployment usually fluctuates between 4-6%) or the housing crisis (about 4 million homes have been foreclosed in the past five years — most of those in just a few states like California, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida —, which is a lot more than normal, but is still a small fraction of the over 110 million homes in America). And contrary to what you say, things were rough in 1992 as well; there was a recession from 1990 to 1991, and unemployment lingered afterwards, getting as high as 7.8% in 1992. That recession wasn’t quite as long or deep as the most recent one, but things still weren’t all that great for many households across America and elsewhere. That didn’t stop millions, including my lower-middle class family, from forking out the modern equivalent of anywhere from $80 to $120 for a new game. Also, your claim about incomes is erroneous. Adjusted for inflation, median household incomes have remained relatively flat over the last 30-something years. While such wage stagnation is not great (they continually rose after WWII on up to the early 70s), it is also not a decrease.

But for the average consumer today, the fact remains that video games cost them less in terms of inflation and less in terms of a percentage of their income. Median inflation-adjusted household incomes for the bottom 90% of earners (i.e., working class and middle class households) have like I said actually remained relatively flat over the last 40 years, with a drop of only a few percentage points since the start of the recession. Meanwhile, inflation-adjusted prices of video games have fallen by anywhere from 30% to 50% over the last 20 years. For most people, $60 is a smaller chunk of their disposable income than it was 20 years ago, meaning that the act of buying a game is easier on the wallet than ever before, especially now that there’s a ton of alternatives to buying brand new. Of course, some people were online complaining about games costing $60 before the recession, and they’ll probably still be complaining after things have finally improved back to pre-recession levels.

But despite the effects of the last recession, most people are still doing as good (or at least no worse) on average as they were 20 years ago, and they’re buying more video games than ever before. The recession didn’t keep Modern Warfare 3 from selling some 26 million copies, nor did it keep people from buying more video games over the last five years than in any prior console generation. In fact, despite the the recession, the 360 and PS3 have experienced steady growth since their debuts, with 2011 being the biggest year so far for either system in terms of both hardware and software sales. As long as that continues to happen, and as long as games keep getting more expensive to develop, game prices will not experience a massive drop. And besides, no consumer good, whether it’s a necessity or a luxury, just drops in price merely to make it more affordable to those who are struggling due to a sudden economic downturn. It’s market forces, not the misfortunes of individual families, that affect what we pay for things. Sony or Microsoft or Activision aren’t going to slash prices of new AAA games to $30-40 just because some people have fallen on hard times, just like how the prices of necessities like food or gasoline or electricity haven’t gone down just to make things easier for everyone. It’s a rough time for many people and it certainly sucks that they’re in such bad shape, but that doesn’t change the fact that games are cheaper than ever and people are buying more games than ever despite the tough economy.

You failed to adjust the minimum wage for inflation as well so your “and minimum wage was much less back then — $5.15/hour vs. $7.25/hour today — so I had to work more hours to buy a game than some part-timer earning minimum wage today would have to work” comment does not hold up.

I don’t need to adjust for inflation in that instance as I’m comparing the amount of time it would take to earn the money to buy a game in 1998 vs. how long it would take in 2012. In 1998, $5.15 and $60 were worth… wait for it… $5.15 and $60 in 1998 dollars. So, when I got my first job in 1998, if I wanted to buy a $60 N64 game it took me 11.65 hours to earn that amount of money since I was being paid $5.15 an hour then (60/5.15≈11.65). Today, it would take 8.28 hours to earn $60 at the current minimum wage of $7.25 an hour (60/7.25≈8.28). If I worked 8.28 hours in 1998 at minimum wage, I’d make under $43 (5.15×8.28≈42.60). That would have been just enough for a new PS1 game that’s at the lower end of the price range for new titles on that system, but not enough to buy, say, Final Fantasy VII or Colony Wars. Going back further, somebody working for minimum wage back in 1992 when the minimum wage was $4.25/hour would have had to work about 16-½ hours to buy the SNES port of Street Fighter II, which retailed for $70 back then (70/4.25≈16.47).

Simple version: Determining how long it would take to earn a game at minimum wage should be applied to the prices shown on the non-adjusted graph as we’re talking about dividing the sticker price of a game in a given year by the minimum wage in that year. Did that help clarify everything?

Interestingly, $5.15 in 1998 dollars is worth $7.25 in 2012 dollars, so inflation has already wiped out the gains made by the increases in minimum wage back in 2007-09.

Pingback: Game cost by inflation | A Random Encounter

500$ for a xbox1x and xbox1s or xbox1 or ps4 and then 60$ for a year of online u take the fact that games are 60 to 100$ now online and u gotta pay for internet on top of paying for the yeasrly subscription to play online which is about on average 60$a month times 12 and u would have spent almost 2 grand on gaming alone today which is a waste of money then now a days you can pay to win so it makesgaming redundant I always played a game to enjoy it and beat it not pay for the accessories or ECT that’s a waste of money if pple can buy upgrades to destroy your character and unlock stuff by paying what’s the point of playing a game anymore I thought playing a game took skill and hours of enjoyment and luck not just pay to play .

Punctuation, son. Use it. Your post is an incoherent mess. I’ll let is slide this time, but if you want to have a conversation, I expect an at least halfway decent attempt at proper punctuation, spelling, etc.

In any case, paying for online is entirely optional, and, by extension, so is buying any kind of DLC, such as microtransactions. I am not subscribed to PSN, and I only play single-player games on my PS4 and Switch. As for internet, presumably most people have the internet already, and don’t simply get it to play online. It’s like adding the cost of electricity into the cost of playing video games.

Also, the Xbox One S and PS4 Slim currently cost less than $300. They are not $500. Only the One X is $500, and that will change eventually as every system gets price cuts. And unless you’re buying a special edition no game costs more than $60 brand new, much less $100. Also, as I pointed out in the article, you don’t have to buy a game brand new day one, and most games typically decline in price over time. If you wait a few months you can probably find a game you want for $40 or less on Amazon.

Pingback: Gamasutra: Raph Koster’s Blog – The cost of games – The Blog Box

Pingback: Raph Koster: The Cost of Games – Games Business Review